MARIA BERMAN was hopelessly smitten with the working fireplace in her first New York apartment, a third-floor walk-up in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn.

Michael Falco for The New York Times

Fran Leadon’s place in Cobble Hill is lighted and aired by transoms.

Librado Romero/The New York Times

Maria Berman treated her nonworking fireplace in Harlem to a new mantel and a marble hearth.

“That fireplace was in use most of the year,” said Ms. Berman, an architect who lived in the apartment in the early 1990s. “For three years I had quarter cords of wood delivered to my doorstep.”

But in 2002, when she moved with a fellow architect named Bradley Horn to an 1898 town house in the Sugar Hill Historic District of Harlem, she gave her heart to another fireplace, one that sat buried in the wall in the front parlor and hadn’t worked for seven decades.

Ms. Berman didn’t care. She discovered a creamy cast-stone mantel at a showroom closeout sale, surrounded the hearth with a toasty slab of Breccia Imperiale marble, and never looked back.

“I don’t miss the fire,” Ms. Berman said. “And I love the look of the surround. It really anchors a room and give it focus.”

When it comes to the attractions of a particular house or apartment, there’s little mystery as to why space-starved New Yorkers are drawn to generous square footage, high ceilings and jaw-dropping views.

But over time, residents find less-obvious design elements unexpectedly alluring, not only faux fireplaces but also weirdly shaped alcoves, decommissioned dumbwaiters, Juliet balconies, claw-foot bathtubs, minuscule shelves carved into staircases, transoms atop doors, brass keyholes and vintage radiators. The list includes even more unlikely details, among them servants’ buttons, speaking tubes, original metal thermostats and shaving closets. (Most people don’t even know what a shaving closet is: a shallow alcove with a sink just large enough for a man to trim his whiskers.)

These mundane grace notes, which may seem to have little purpose beyond collecting dust, are sometimes the very things residents single out to explain why they are drawn to a particular space. On occasion, these homely accents even prove to be the selling point when it comes to closing a deal.

“I once had a client who said they decided to buy because of the servants’ call buttons on the floor of the dining room,” said Mike Lubin, a vice president and director of Brown Harris Stevens. “They just fell in love with them.”

The apartment in question, on the Upper West Side, was what is known as an Edwardian 5; these early-20th-century bachelor’s quarters included a living room, a dining room, a bedroom, a kitchen and a maid’s room for the person whose duties included serving dinner to the man of the house.

“I’ve also had people tell me they’re buying an apartment because of the original windows,” Mr. Lubin added. “Once a person said, ‘I really like the brass doorbell.’ ”

Whether the doorbell clinched the deal is unknown, but clearly it didn’t hurt.

Simeon Bankoff, who as executive director of the Historic District Council knows a thing or two about the allure of history, counts himself fortunate to have a window in the broom closet of his 1905 brick row house in Windsor Terrace, Brooklyn. Not to mention an odd set of finials in a corner.

“These things just made us like the place more,” Mr. Bankoff said. “These details are like a beauty mark on a face. We like them for the same reason people liked follies. They’re small, cute and useless.”

Scholars and others who analyze why New Yorkers are so enamored of these accents invariably end up talking about the mysterious pull of the past.

“Even in the ‘20s and ‘30s, when people had central heating, it was a risk for developers to build without fireplaces,” said Sandy Isenstadt, an architectural historian and a fellow at the Institute for Advanced Study in Princeton, N.J., who studies the significance of items like picture windows. “They weren’t functional, but they had symbolic value.”

Many of these touches perked up otherwise undistinguished living quarters — “like a brightly colored tie with a drab suit,” as Mr. Isenstadt put it — and he attributes the appeal of these accents in part to their individual, almost cozy scale. “A small window fit your face,” he said. “A shaving closet was made for use by one person at a time.”

Akiko Busch, an essayist who explored the significance of the domestic environment in a collection titled “Geography of Home: Writings on Where We Live,” calls the phenomenon “the usefulness of the useless.”

“Take the Juliet balcony,” Ms. Busch said. “Today, none of us have lives that make use of such a thing. But having such a balcony puts us in touch with people who did lead such lives. Momentarily, we’re someone else.

“These balconies, along with things like claw-foot tubs and old radiators — they’re not particularly functional, but they’re vestiges of the life of the apartment,” she added. “They resonate with history, with a sense of continuity. As Americans, we’re starved for that.”

Dexter Guerrieri, the president of Vandenberg, the Townhouse Experts, a Manhattan real estate firm that specializes in high-end properties, is acutely aware of the appeal of these small-scale details.

“I love those little things,” said Mr. Guerrieri, who has a particular fondness for the recessed brass lifts in the window sashes in his Brooklyn Heights town house. He also has a soft spot for the crystal doorknobs affixed to brass plates punctuated by small keyholes.

In the fact sheets that his office draws up to describe various properties, he makes a point of highlighting such accents. The description of a $5 million town house on West 90th Street notes that “under the historic side stoop there is a sealed storage room with an arched half-moon-shaped window facing the street.”

The description of a town house at 47 West 92nd Street cites “original brass knobs” on doors. A third fact sheet mentions “some truly Victorian curiosities, such as a system of dumbwaiters, maid’s bells and speaking tubes. ”

“I see people notice these things and smile,” Mr. Guerrieri said. “People are not always articulate about why they like them, but you see clients respond to these frills.”

And a purely decorative fireplace? “People will make a note of it and ask if it works,” he said. “But if I say no, they don’t seem to care. Because even if a fireplace works, many people don’t use it very often. It’s just too much trouble, with all that dust in your face.”

Such touches are typically found in prewar buildings, in part because cheaper construction costs encouraged developers to include embellishments. But they can also be seen in many of the houses that Mary Kay Gallagher, the president of a firm that bears her name, shows clients in Victorian Flatbush, Brooklyn.

“I see the eyes of potential buyers light up when they see these things,” Ms. Gallagher said. “Old radiators? People love them. Phone tubes? They say they’ll leave them where they are. Old brass gas extensions? They say that’s part of the charm.”

And abandoned fireplaces?

“They might add a couple of thousand dollars to the price,” Ms. Gallagher said. “They might even help you make a sale. People say they can put plants in them.”

The appeal of the faux fireplace, a powerful reminder of the traditional, comforting hearth, is particularly telling. For decades, one of the most sought-after items in New York apartments and town houses was what real estate advertisements shorthanded as the WBFP. The abbreviation conjured visions of a roaring wood fire on a chill winter’s night. Close your eyes, and you were practically a Pilgrim.

But when the WBFP began falling out of favor in the late 20th century, without missing a beat many people transferred their affections to faux alternatives — hearths that burned with gas and sometimes with nothing at all.

The fireplace resonates so powerfully that architects are occasionally asked to design nonworking fireplaces. Even the memory of a fireplace can add cachet. Many New York apartments have leftover mantelpieces. And far from finding them an eyesore, residents say that these fireplace “ghosts” remind them of a lost grandeur in residential living.

In a fast-changing city like New York, the appetite for signs of a vanished era may be especially strong.

“There are so many romantic notions surrounding what it’s like to live in New York,” said Mr. Lubin of Brown Harris Stevens. “It’s a dream come true, a sign that you’ve made it. That’s the appeal of little foyers that are so small, you can’t put a stick of furniture in them. They give people the sense that they’re living in a 10-room Park Avenue apartment.”

These details also remind people that they’re living in quarters that could have been occupied by characters out of Edith Wharton, even if it’s children who these days occupy most onetime servants’ rooms.

Along with attracting potential buyers and renters, architectural idiosyncrasies can also anchor existing residents. This is the case in the apartment in Cobble Hill, Brooklyn, where Fran Leadon, an author of the 2010 edition of the AIA Guide to New York City, lives with his wife, Leigh Anderson, the author of the coming “Ultimate Game Book for Grownups.”

Old-fashioned transoms over the doors bring in light and air. And there’s more: “I have a pointless nook in the hallway made by a slanted wall that is actually my favorite part of the apartment,” Mr. Leadon said.

“I don’t know why it’s there, but I put a tall, skinny plant stand in the space and a little oil painting of Florida,” added Mr. Leadon, who grew up in the state. “It’s become kind of like a little Florida shrine.”

At times, inconvenience would seem to outweigh charm. Fitting shower curtains around an ancient claw-foot bathtub is a considerable challenge. A Juliet balcony has space for, at best, a few pots of geraniums. And let’s be honest: who needs a mothballed dumbwaiter?

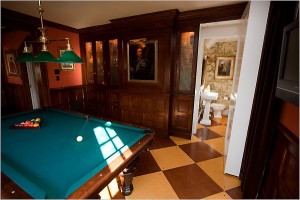

Yet such touches are sometimes added as a happy afterthought. When Lon and Michelle Otremba were modernizing their Tudor-style house in Douglas Manor, Queens, they asked their architect, Kevin Wolfe, to conceal a new powder room behind a paneled wall in the billiard room. To open the door, guests pull an almost invisible lip of wood trim.

The room, born of necessity and a reminder of the secret spaces sometimes found in residences created many decades ago, is Ms. Otremba’s favorite part of the house.

“I wish it had a history,” she said. “But it’s totally charming. I think it’s just the fact that it’s a secret.”

Link: http://www.nytimes.com/2010/04/04/realestate/04cov.html?pagewanted=all

Are you interested in buying a New York Brownstone? For more information on NY townhouses and New York City Brownstones for sale , contact Vandenberg — The Townhouse Experts TM. We specialize in townhouse realty.